IBD, PLE, Lymphangiectasia and Maltese - What I Wish I Had Known

-Julie Osborn, OTR and Leigh Updike Braun

Inflammatory Bowel Disease. In humans, this is defined as either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s Disease. In dogs, the definition is somewhat nebulous and is considered a syndrome, not a disease, consisting of an array of symptoms. Sometimes referred to as chronic enteropathy, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in dogs is primarily characterized by chronic inflammation (duration longer than 3 weeks) of the small intestines, although the colon (large intestine) may also be involved. While it is known that the inflammation is caused by the accumulation of inflammatory cells in the intestinal mucosa, the underlying cause of IBD is not fully understood.

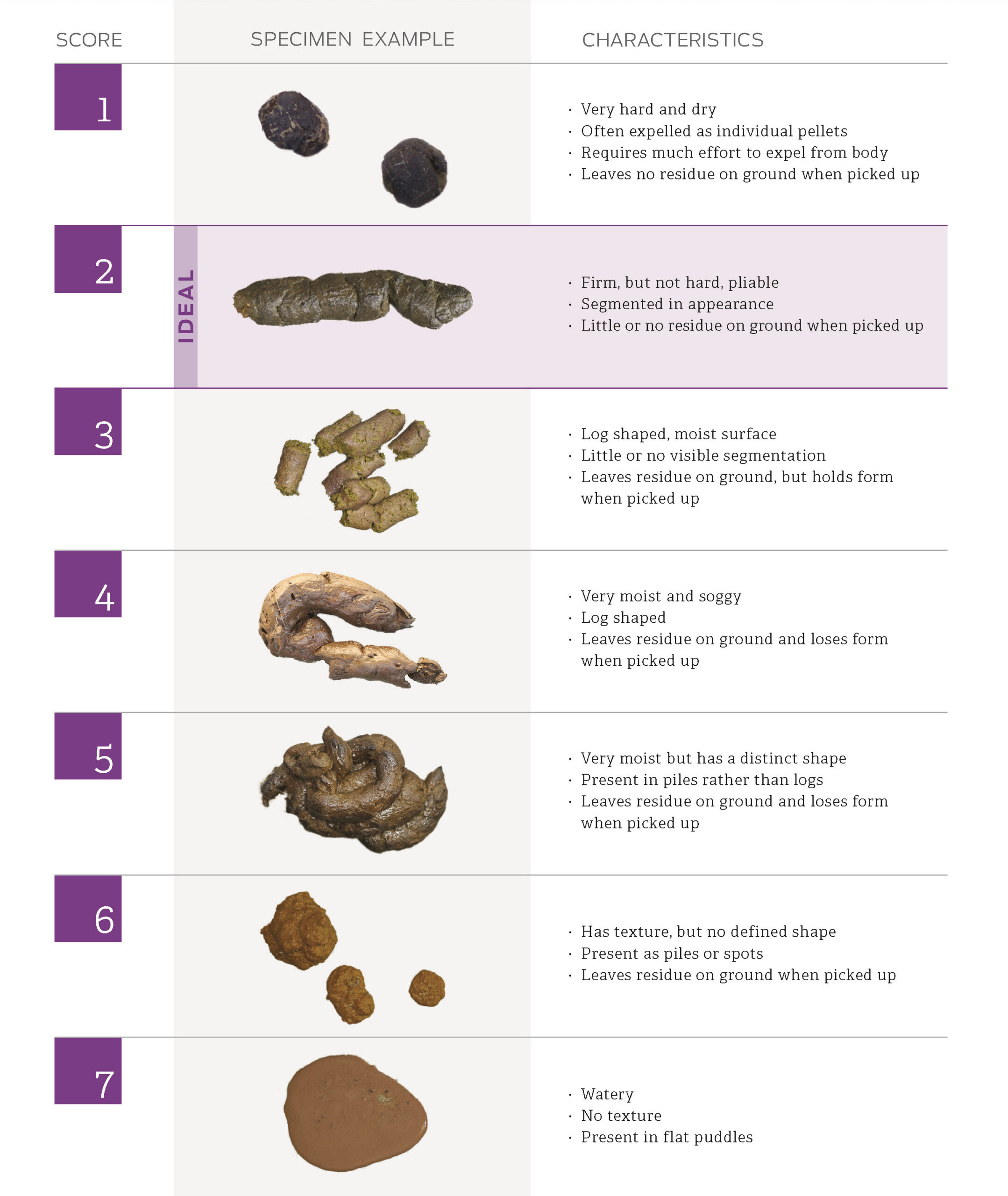

Symptoms of IBD include diarrhea (consistent or inconsistent), emesis (vomiting), often foamy type emesis, abnormally and inconsistently formed stools, bloody stools, mucous stools, flatulence, abdominal rumbling, loss of appetite or increased appetite (from malabsorption of nutrients in the small intestine), weight loss, anemia, abdominal pain, and lethargy. Not all dogs present with the same symptoms, which makes the diagnosis of IBD challenging. A dog’s stool should be similar to a human’s stool in regard to form and consistency (Figure 1). Alterations in your dog’s stool patterns should be of concern and should be discussed with your veterinarian at early onset.

The various forms of IBD are classified by anatomic location and the predominant cell type involved. Lymphocytic-plasmacytic enteritis is the most common form in dogs and cats, followed by eosinophilic inflammation2. Your veterinarian will assess your dog’s condition based on symptoms and will conduct tests to rule out differential diagnoses including lymphoma and foreign body obstruction. A diagnosis of IBD is best determined by tissue biopsies of the small intestine via endoscopy.

Figure 1. Fecal Scoring Chart, Purina Institute, 2022.

Chronic inflammation of the mucosal lining of the intestines from inflammatory bowel disease can lead to Protein-Losing Enteropathy (PLE). Protein-Losing Enteropathy is a serious condition in which the protective mucosa of the small intestine becomes disrupted by intestinal inflammation and/or lymphatic dysfunction, and plasma proteins (albumin and globulin) are lost through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Albumin is produced by the liver and is of great concern with PLE, as it is typically lost at a quicker pace than globulin. When a dog develops PLE, the liver is unable to generate sufficient amounts of albumin to compensate for the loss of albumin occurring in the GI tract. When symptoms progress and become severe, fluctuations and disruptions in cellular pressure cause fluid to leak out of the dysfunctional cells into the body, resulting in the accumulation of fluid in the abdomen (ascites), chest cavity (pleural effusion) and legs (dependent edema). This leads to generalized discomfort, decreased breathing capacity, and difficulty walking. PLE may also be silent so it is imperative to strictly monitor your dog’s symptoms of IBD once it is diagnosed.

Sudden death caused by blood clots occurs in PLE and can manifest in dogs that have clinically “silent” disease. The mechanism is not well defined, but suggested causes of PLE-associated thrombosis include systemic inflammation, altered vitamin K absorption, loss of antithrombin III, hyperaggregation of platelets, hyperfibrinogenemia, and vascular compromise4.

Primary and secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia are both cited to affect Maltese. While primary lymphangiectasia is classified on its own as a primary disorder, secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia is a result of IBD and PLE and is therefore classified as a secondary disorder. Both types of lymphangiectasia are characterized by dilation of the lymph vessels in the small intestine. Tiny lymph vessels, known as lacteals, are specific to the small intestine and absorb fats from foods that are eaten. When the lacteals become inflamed, they dilate and rupture, losing the lymph (the fats, cells, and proteins inside of them) to the intestinal tract. When primary or secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia becomes prevalent throughout the small intestine, the result is malnutrition, leading to loss of appetite, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of muscle mass and loss of fat. The abdomen and chest cavity will subsequently accumulate fluid, causing discomfort and difficulty breathing. The abdomen will look and feel distended. Sadly, dogs with either primary or secondary lymphangiectasia are prone to developing blood clots, which, when dislodged, can lead to death.

The 2022 American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care curative guidelines have established dogs with PLE as “at risk” for thromboembolic disease6. Owners of dogs diagnosed with IBD, and subsequently PLE and primary or secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia, should keep a close watch on their dog’s lab values, particularly the platelet counts and antithrombin levels, as rising platelet counts and platelet masses, as well as low antithrombin levels can lead to the development of blood clots that travel to the dog’s brain or lungs, resulting in life threatening conditions or death.

The 2022 Update on the Consensus on the Rational Use of Antithrombotics and Thrombolytics in Veterinary Critical Care cites a “moderate to strong association between PLE and thrombosis3,” with both venous and arterial thrombotic complications occurring, with venous thrombi being the more prevalent of the two. With recent evidence suggesting a “moderate to strong link between a diagnosis of PLE in dogs and the development of thrombotic complications, many of them life-threatening or fatal,” and findings suggesting “that thrombosis is an important complication of PLE,” the March 2022 veterinary guidelines now “recommend antithrombotic therapy for all dogs with protein-losing enteropathy unless the risks (particularly gastrointestinal bleeding) are deemed to outweigh the potential benefit in individual patients”3.

Maltese are unfortunately cited as a breed that is predisposed to IBD, PLE and both primary and secondary lymphangiectasia. Genetics plays a role in IBD, and research is ongoing to determine the exact cause of its ambiguous nature. A proactive approach to your dog’s management is critical, and early detection of IBD should lead to a greater lifespan. Attention should be given to your dog’s lab values, particularly to the albumin levels, globulin, albumin/globulin ratios, total serum protein levels, vitamin B12 levels, calcium levels, cholesterol levels, platelet counts and platelet volume levels. Ask for your dog’s lab values after blood is drawn and keep a spreadsheet on your dog’s labs so you can watch for irregularities or patterns as your dog ages.

It is imperative that you engage and adhere to a diet protocol and possibly a medication regimen with your veterinarian’s guidance when your dog is diagnosed with IBD. Hypoallergenic diets are typically recommended for dogs with PLE while low-fat diets are recommended as the standard course of care for dogs with intestinal lymphangiectasia. Dogs diagnosed with both PLE and intestinal lymphangiectasia may be best managed by implementing home cooked diets. Common dietary antigens in commercial dog foods, including wheat, gluten, soy, lactose, beef, and chicken proteins, have been suspected of playing a role in disease pathogenesis. Strict hypoallergenic diets include novel protein diets (prescription exclusion diets) and hydrolyzed protein diets. Novel protein diets simply contain a protein source to which the animal has not been exposed2. Many of these prescription and novel protein diet foods are available to veterinarians and should be discussed with them. If the dog’s gastrointestinal system becomes sensitized to the novel protein source, then it is recommended to switch to a second hypoallergenic diet after 6 to 8 weeks of successful therapy5.

While pharmacological intervention for PLE and intestinal lymphangiectasia often focuses primarily on immunosuppressive medications that may be administered in conjunction with the dietary modifications noted above, there is little evidence to support the use of immunosuppressive medications for the course of care for these dogs as there is no convincing scientific evidence that the cause is autoimmune or immune-mediated. Commonly prescribed immunosuppressive medications include prednisone, prednisolone, azathioprine, cyclosporin, chlorambucil and methotrexate. The adverse effects of corticosteroid treatment in dogs, that is muscle protein catabolism, thrombosis, and hyperlipidemia (with potential for lymphatic expansion) are particularly disadvantageous in PLE, and their use is somewhat counterintuitive1. Anti-inflammatory doses of steroids to limit the inflammation associated with the lymphatic disease, along with diet modification should be the choice for the course of care6. Prebiotics and probiotics may also be implemented as adjunctive therapies. Close attention should be paid to the potential side effects of the medications administered to your dog, and close contact with your veterinarian should be maintained in efforts to minimize medication side effects and determine the best course of care for your dog.

It is with great hope that we can educate other Maltese owners to better recognize and understand the warning signs of IBD, PLE and lymphangiectasia, so that lives are better lived, and lifespans are prolonged. We are hopeful that genetic markers for IBD, PLE and intestinal lymphangiectasia will soon be identified, as have been identified with Protein Losing Nephropathy (caused by kidney disease rather than IBD), so that better breeding standards may be established for our dogs.

This article is written in memory of Lucy, Hallie, Princess and Snoopy.

Citations:

- Craven MD, Washbau RJ. Comparative pathophysiology and management of protein-losing enteropathy. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 33(2), 383─402. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15406, 2019.

- Defarges A. Chronic Enteropathies in Small Animals. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Merck Manual Veterinarian Manual. 2020.

- deLaforcade A, Bacek, L, et al. 2022 Update of the Consensus on the Rational Use of Antithrombotics and Thrombolytics in Veterinary Critical Care (CURATIVE) Domain 1- Defining populations at risk. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. DOI: 10.1111/vec.13204, Revised March 31, 2022.

- Fogle J, Bissett A. Mucosal Immunity and Chronic Idiopathic Enteropathies in Dogs. Compendium Vet. 2007.

- Guilford WG, Strombeck DR: Strombeck’s Small Animal Gastroenterology. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1996.

- Jablonski, Wennogle SA. Michigan State University, 2022.

Additional References:

- Brooks W. Intestinal Lymphangiectasia (Protein-losing Enteropathy) in Dogs. Veterinary Partner. Originally Published 2003, Revised 2021.

- Cohn, Cote’. Lymphangiectasia. Clinical Veterinary Advisor: 4th edition. 2020.

- Dossin O, Lavoue’ R. Protein-losing enteropathies in dogs. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice. 41(2), 399─418. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.02.002. 2011.

- First Vet. “Protein Losing Enteropathy in Dogs.” 2022. https://firstvet.com/us/articles/protein-losing-enteropathy-in-dogs.

- Keuhn NF. Pulmonary Thromboembolism in Dogs. Merck Manual Veterinarian Manual. 2018.

- Ortiz LG. “Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Dogs-Symptoms and Treatment.” Animal Wised. 15 March 2022. https://www.animalwised.com/inflammatory-bowel-disease-in-dogs-symptoms-and-treatment-4092.html.

- Silvio D, de la Motte C, Fiocchi C. Platelets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clinical, Pathogenic, and Therapeutic Implications. American Journal of Gastroenterology.99(5), 938-945. 2004.

- Voudoukis E, Karmiris K, Koutroubakis IE. Multipotent role of platelets in inflammatory bowel diseases: a clinical approach. World Journal of Gastroenterology. Doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3180. 2014.

- Weir M, Downing R. “Protein-Losing Enteropathy (PLE) in Dogs.” VCA Animal Hospitals. 2022. https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/proteinlosing-enteropathy-ple-in-dogs.

- Yan S LS, Russell J, Harris NR, Senchenkova EY, Yildrim A, Granger DN. Platelet abnormalities during colonic inflammation. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. 19(6): 1245-1253. Doi: 10.1097/MID.0b013e318281f3df. 2014.

- Yoshida H, Granger DN. Inflammatory bowel disease: a paradigm for the link between coagulation and inflammation. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. 15(8): 1245–1255. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20896. 2010.